World’s first low cost dialysis

It’s an invention that could save millions of lives each year and transform the way kidney disease is treated around the world.

After a year-long global quest, the world’s first low cost dialysis system was unveiled on World Kidney Day, 10 March 2016.

Vincent Garvey was awarded the Affordable Dialysis Prize and took home US$100,000 for his innovative design. Garvey’s dialysis system can fit into a small suitcase and uses a standard solar panel to power a highly efficient, miniature distiller capable of producing pure water from any source.

Conventional dialysis systems cost several tens of thousands of dollars. They are widely available in most developed countries but much less so in countries with limited funds for healthcare. Research published in The Lancet found that while more than nine million people in the world need dialysis for terminal kidney failure, only 2.61 million currently get this life-saving treatment.

The prize was jointly established by The George Institute for Global Health, the International Society of Nephrology and the Asian Pacific Society of Nephrology and supported by the Farrell Family Foundation.

Garvey, a manufacturing engineer from the United Kingdom’s Isle of Man, had little knowledge of dialysis when he entered the competition, but was inspired by the chance to save lives.

Mr Garvey said:

“I have always loved a challenge and the idea of solving this problem excited me from the start. It’s incredible to win this prize but I am already focused on building the team to tackle the challenges ahead.”

Professor Vlado Perkovic, Executive Director of The George Institute, Australia, said the judging panel, made up of nine global dialysis experts, was unanimous in its decision.

Professor Perkovic said:

“Dialysis has been with us for more than 50 years but there has been no great leap forward in its design or, more importantly, its cost, remaining hugely expensive and out of reach for millions of sick people.

“This invention just might be the radical overhaul we’ve all been hoping and waiting for.”

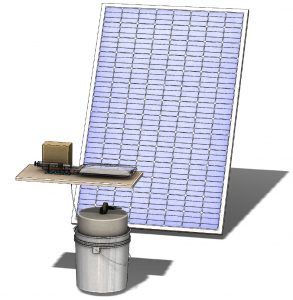

The water purifier, care station and solar panel.

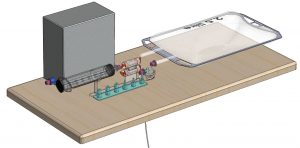

A close-up of the care station.

The entire device can fit inside a small suitcase.

How does the winning design work?

Vincent Garvey’s winning dialysis system recognises the critical barrier to affordable dialysis is the lack of cheap, sterile water in countries where the electricity supply is unreliable and water sources may be contaminated. Using a standard solar panel, it heats water taken from any local source to make steam, which is used not only to sterilise the water but also to fill empty peritoneal dialysis (PD) bags under sterile conditions. PD is potentially much cheaper than haemodialysis, but in poor countries the cost of transporting thousands of foreign manufactured two litre bags of PD fluid to remote locations can make it prohibitive.

The winning entry will be just as useful for short term dialysis for acute kidney failure, supporting children and young adults whose kidneys have stopped working temporarily due to infection or dehydration, and for whom just a few days of dialysis can be lifesaving. The design also offers detailed plans on how the system could be used for affordable haemodialysis, the more common type of dialysis.

Why do we need a low cost dialysis system?

Research published by The George Institute in 2015 revealed that millions of people globally die unnecessarily every year because they cannot access treatment for kidney failure (dialysis or a kidney transplant).

The report showed 2.61 million people around the world were on chronic dialysis for terminal kidney failure but as many as seven million people more could be missing out on life saving treatment.

Most of these preventable deaths occurred in China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Nigeria.

In India 70 per cent of people with chronic kidney disease live in rural areas, with limited access to treatment. It’s estimated that less than 10% of all patients who need it receive any kind of renal replacement therapy in India.